INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution establishes health as a fundamental human right, urging countries to provide accessible, affordable healthcare (WHO, 2022). The right to mental health has therefore steadily gained global recognition, playing a crucial role in the well-being of individuals and populations (United Nations, 2020). Depression ranks as a leading contributor to disability, while suicide is a major cause of death across the lifespan (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2019; WHO, 2023). The impact of severe mental health conditions on overall health is significant, resulting in a potential reduction of up to two decades of life expectancy (Liu et al., 2017). Paradoxically, despite its impact and association with heightened violence, poverty, and social exclusion, mental health remains insufficiently addressed within public health discourse (WHO, 2023).

In keeping with the WHO call for countries to allocate sufficient resources for universal healthcare, the Mexican Constitution establishes the right to health protection for all individuals, including those lacking social security (Secretaría de Salud de México, 2015). However, Mexico’s healthcare system shows substantial disparities, distinguishing between uninsured individuals and those with public insurance coverage (72% of the population).

Most of the Mexican population is insured by two public institutions: the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (Mexican Institute of Social Security; Spanish acronym IMSS) and the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado (the Mexican Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers; Spanish acronym ISSSTE). IMSS, covering 47.8% of the population, primarily serves the formal private sector, including employees, their families, retirees, pensioners, and voluntary members. ISSSTE, insuring 16.7% of the population,1 focuses on federal, state, and municipal government employees, together with their families and retired public sector workers. The demographic composition of the populations insured by IMSS and ISSSTE varies. In IMSS, 25.1% are under 20, 56.8% are between 20 and 59, and 18.1% are 60 and over.1 Conversely, 25.7% of ISSSTE’s insured population are under 20, 41.9% are between 20 and 59, while a higher proportion, 32.4%, are 60 and over.1 Both of these institutions are funded through employee and employer contributions, government subsidies and fees for certain services (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 2021). The remaining percentage (approximately 7.5%) of Mexicans insured by the public sector receive coverage through public institutions such as SEDENA (Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional/Secretariat of National Defense), SEMAR (Secretaría de Marina/Secretariat of the Navy), and Pemex (Petróleos Mexicanos/Mexican Petroleum). This diversification reflects the segmented nature of Mexico’s healthcare system, providing specific coverage by employment sector. The complexity of Mexico’s healthcare system is further borne out by the inclusion of other public institutions: Centros de Integración Juvenil (Youth Integration Center; Spanish acronym CIJ), which focus on addiction treatment for youth, and the Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia (System for Integral Family Development; Spanish acronym DIF), a public institution for family welfare. The system also distinguishes between IMSS, providing formal sector employees with health and social security benefits, and IMSS Bienestar, serving informal sector workers and rural populations. These distinctions reflects the diverse healthcare needs and sector-specific services within Mexico.

The uninsured Mexican population, primarily comprising informal job sector workers, the unemployed, and their dependents, has limited access to healthcare, mostly provided by the Secretaría de Salud (Ministry of Health, Mexico; Spanish acronym SS). Although private medical services, encompassing physician care, pharmacies, and hospitals, are available, their accessibility is limited to a small proportion of the population due to their elevated costs (Espinola-Nadurille et al., 2010; Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 2021; WHO et al., 2020). Further barriers to healthcare access in Mexico include a lack of services in rural areas, home to 21% of the population (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía[INEGI], 2021). Recent changes in insurance systems and public policies (such as the transition from the Seguro Popular [Popular Insurance Scheme] to INSABI [Instituto de Salud para el Bienestar]) have led to a significant increase in healthcare access issues, with a noticeable rise in the population lacking healthcare access. This issue disproportionately affected rural areas, where public health services not tied to employment benefits are more common, highlighting the vulnerability of these communities to policy changes in the healthcare system (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social[CONEVAL], 2021).

Historically, Mexican health policies have tended to overlook mental health, leading to significant diagnostic and therapeutic gaps, as well as uneven service availability across the country (Secretaría de Salud de México, 2023a). Recent data indicate that up to 80% of individuals with mental and substance use disorders in Mexico fail to receive adequate care (Secretaría de Salud de México, 2022). This figure reflects the gap between those suffering from a disorder and those who obtain proper treatment in healthcare services. Barriers to mental healthcare are complex and persist in most regions globally, including a range of personal, cultural, and structural factors, such as stigma and social attitudes, lack of awareness and education, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure (Carbonell et al., 2020). A critical aspect of this issue, and the focus of the current study, is the inadequate distribution of mental health providers, such as psychiatrists and psychologists, which significantly impacts the accessibility and effectiveness of mental healthcare services.

The insufficient allocation of mental health providers in Mexico has raised concerns, as documented in national and international reports (Pan American Health Organization [PAHO], 2023; PAHO, WHO & Secretaría de Salud de México, 2011; Secretaría de Salud de México, 2022). According to WHO, in 2016, there were .2 psychiatrists, 2.2 nurses, .5 social workers, and 3.5 psychologists per 100,000 population working in the mental health sector in Mexico (WHO, 2019). In 2018, a census found 4,999 psychiatrists working across the country, yielding a ratio of 3.7 psychiatrists per 100,000 population (Heinze et al., 2019), below the minimum ratio of five psychiatrists per 100,000 population recommended by WHO (2014). Moreover, about 60% of all psychiatrists are concentrated in Mexico’s three largest cities, exacerbating regional disparities in mental health care access (Heinze et al., 2019). At the same time, according to the Ministry of Economy, approximately 67,700 psychologists currently work in clinical settings in Mexico, yielding a ratio of 53.7 per 100,000 population (Secretaría de Economía, 2023). However, it should be noted that since these ratios encompass both public and private sector practitioners, the accessibility of mental healthcare for a sizable portion of the population is probably overestimated.

A sectoral plan for mental health and substance use disorders has therefore been developed (Secretaría de Salud de México, 2023b), including institutions such as the SS, IMSS and ISSSTE. This strategic plan seeks to unify and synergize fragmented efforts across sectors into a cohesive, collaborative initiative. It encompasses institution-specific initiatives and the establishment of integrated mental health service networks. The goal is to enhance equity, effectiveness, efficiency, and quality in mental healthcare, thereby contributing to both individual and community well-being. However, an updated, detailed assessment of mental health personnel within Mexico’s public sector is lacking, despite being essential to accurately evaluating the mental health provision gap.

In this study, we sought to characterize the shortage of mental healthcare providers, specifically psychiatrists and psychologists, within the Mexican public sector. To this end, we described and analyzed the geographical distribution of public health facilities employing these professionals, the healthcare provider ratio per 100,000 population, the proportion working in inpatient and outpatient settings, and their employment in public insurance systems.

METHOD

1. Study design

This study is a secondary data analysis focused on mental health providers at public healthcare centers (clinical facilities operating within public institutions) in Mexico.

2. Sample description

The totality of public healthcare centers in Mexico employing at least one psychiatrist or one psychologist, across all levels of care, were included in the study. Healthcare centers from the following public institutions were considered for analysis: SS, IMSS, ISSSTE, SEDENA, SEMAR, Pemex, CIJ, DIF, IMSS Bienestar, State Medical Services, Municipal Medical Services, and University Hospitals.

3. Measurements

Data are drawn from the Subsistema de Información de Equipamiento, Recursos Humanos e Infraestructura para la Atención de la Salud (SINERHIAS, Healthcare Information on Equipment, Human Resources, and Infrastructure Subsystem,2 https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset?tags=sinerhias), database, including data from the latest version available at the time of analysis (updated at the end of June 2023). The following data were collected, considering each center in the sample: number of psychiatrists and psychologists employed, localization (using the Cartesian coordinate system), public insurance system, and type of facility (inpatient or outpatient).3

4. Statistical analysis

We reported the total number and percentages of mental health providers employed at public health centers, their affiliation to various public institutions, and their distribution across inpatient and outpatient clinics. The population ratio of psychiatrists and psychologists per 100,000 population was calculated using the 2023 population projections of the National Population Council (CONAPO, 2023). Our analyses include a nationwide perspective and a breakdown of the data by state.

5. Ethical considerations

This study employs an updated version of a publicly available database. This updated version, which also includes the location of the healthcare facilities, was requested by the authors from the General Directorate of Health information (DGIS) within the SS. No personal information on mental health providers was obtained at any point in the study.

RESULTS

1. Psychiatrists at public institutions

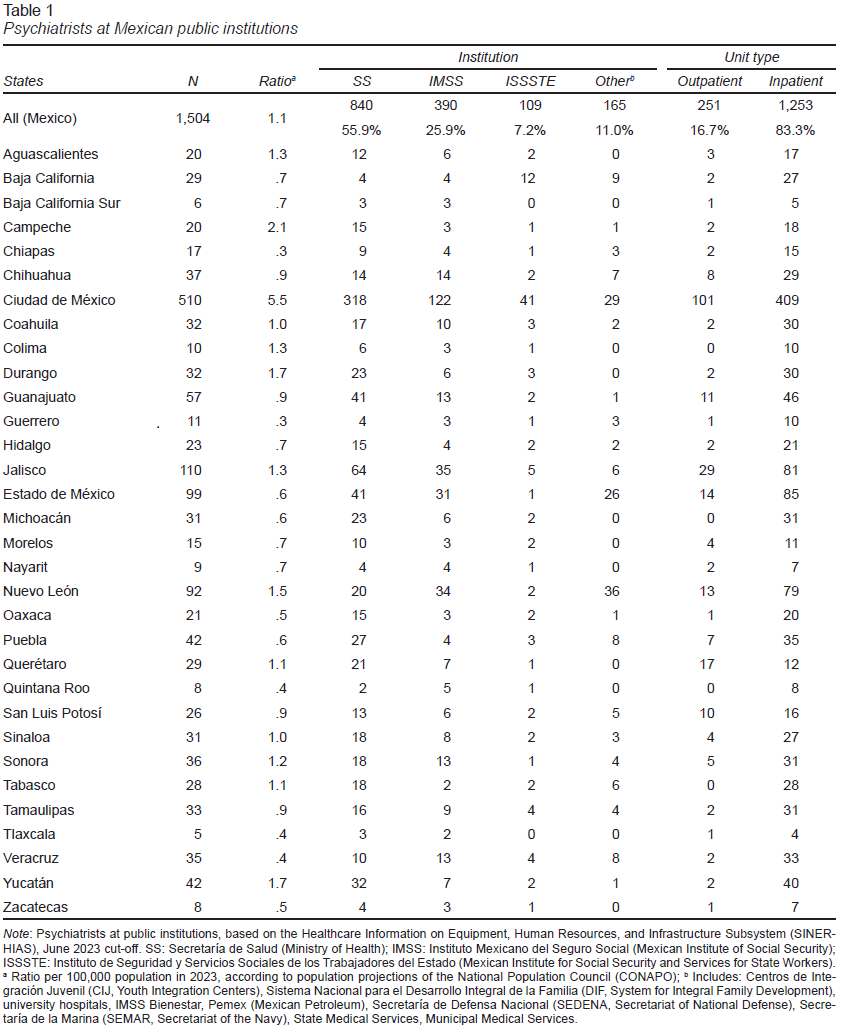

As of the first half of 2023, Mexico had 1,504 psychiatrists working at public institutions, resulting in a ratio of 1.1 per 100,000 population. In terms of public institutions, the SS employed the largest share, with 55.9%, followed by IMSS with 25.9%, and ISSSTE with 7.2%. The remaining 11.0% worked at other public institutions (Table 1). Regarding their practice settings, 16.7% of psychiatrists operated in outpatient clinics, while the majority, 83.3%, worked at inpatient units (Table 1). This prevalence of inpatient clinics for psychiatrists was consistent across all insurance systems, with 79.2% in the SS, 95.5% in IMSS, 86.1% in ISSSTE, and 73.3% in other public institutions (Table 1).

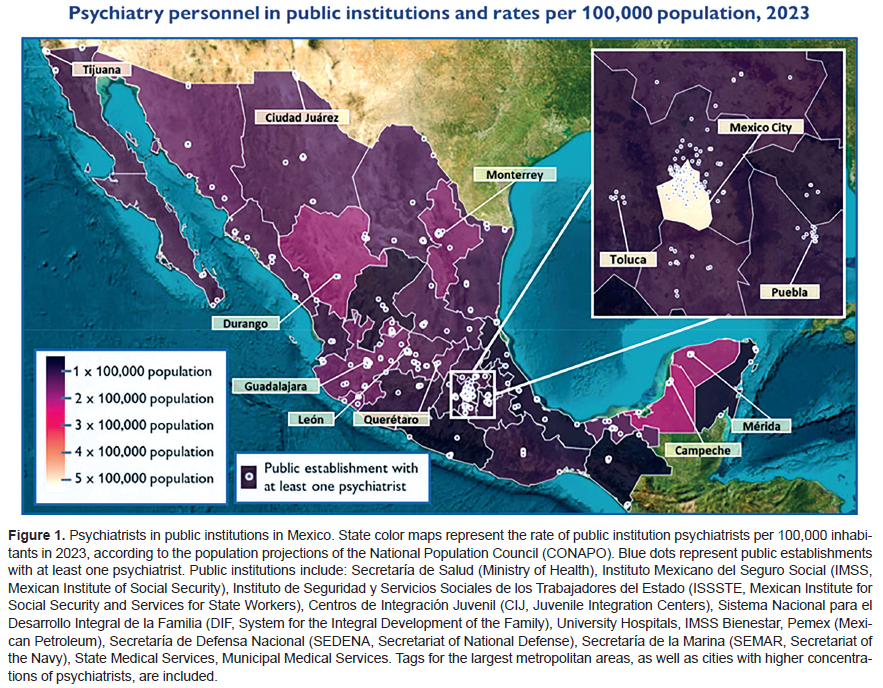

The distribution of public sector psychiatrists across states showed significant disparities (Table 1, Figure 1). Mexico City recorded the highest concentration, with a ratio of 5.5 psychiatrists per 100,000 population, followed by Campeche with 2.1, and Durango with 1.7. Conversely, states with the fewest public sector psychiatrists included Chiapas and Guerrero, both registering a ratio of .3 psychiatrists per 100,000 population, as well as Quintana Roo, Tlaxcala, and Veracruz, all with a ratio of .4.

Table 1 and Figure 1 provide detailed information on the number and ratio of public sector psychiatrists per state, their institutional affiliation, setting, and the geographic location of the centers where they are employed.

2. Psychologists at public institutions

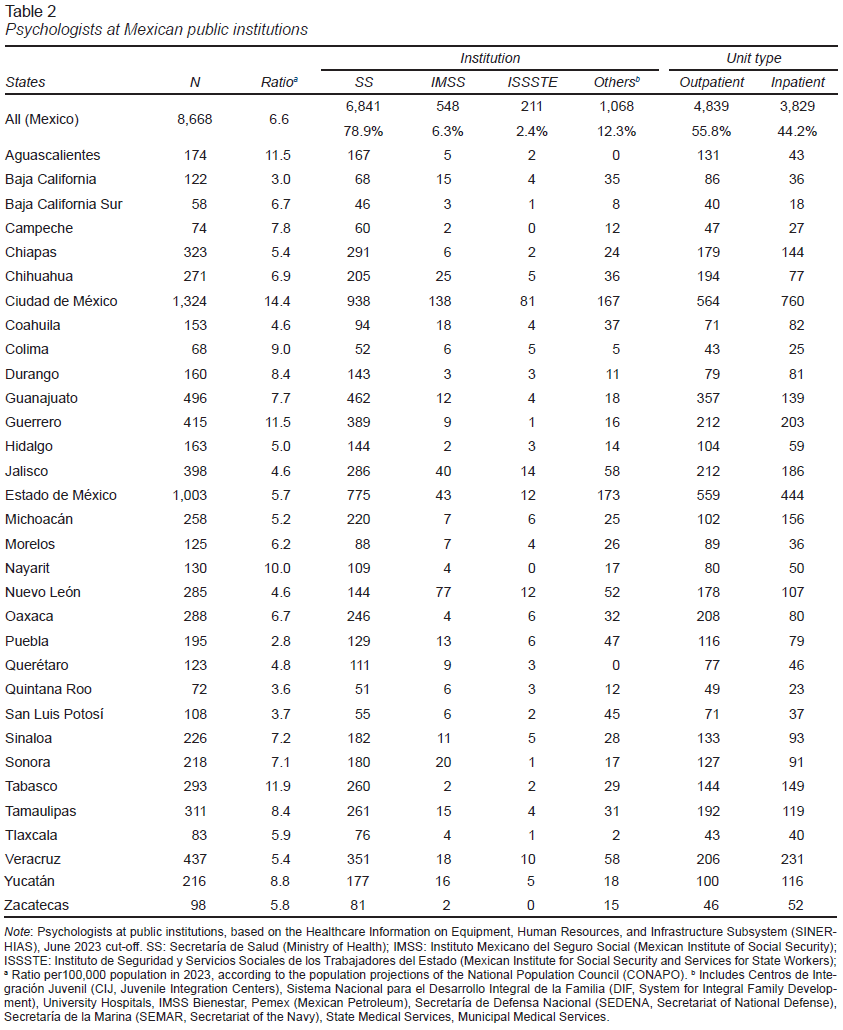

As of the first half of 2023, there were 8,668 psychologists in Mexico practicing at public institutions, yielding a ratio of 6.6 psychologists per 100,000 population. The SS employed the majority, 78.9%, followed by IMSS with 6.3%, and ISSSTE with 2.4% (Table 2). The remaining 12.3% worked at other public institutions.1 In regard to practice settings, 55.8% of public sector psychologists worked at outpatient clinics and 44.2% at inpatient facilities (Table 2).

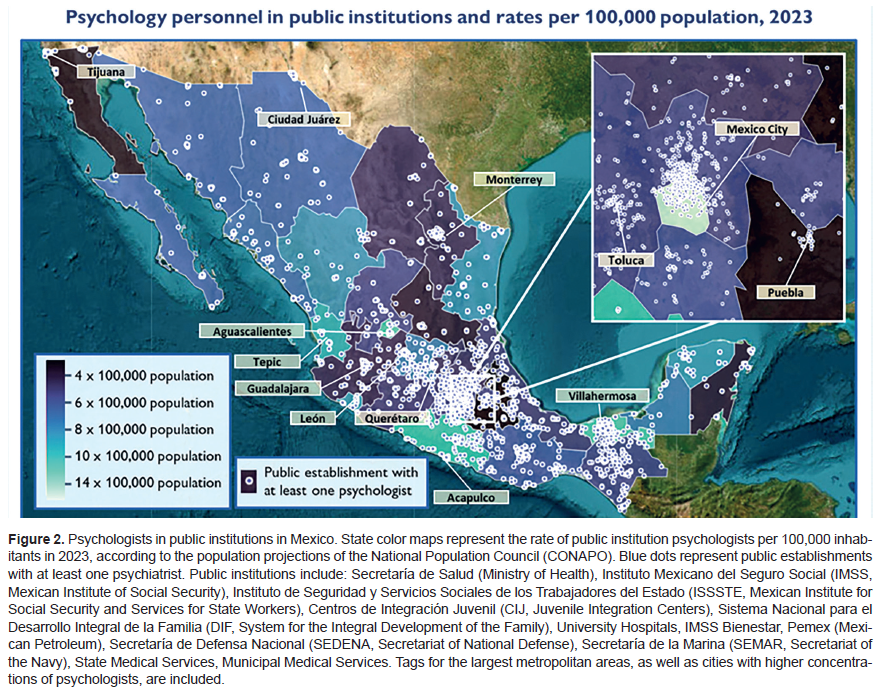

An uneven distribution of public sector psychologists among Mexican states was observed (Table 2, Figure 2). Mexico City had the highest concentration, with a ratio of 14.4 per 100,000 population, followed by Tabasco with 11.9, and Aguascalientes and Guerrero, both with 11.5. In contrast, states with the fewest public sector psychologists included Puebla and Baja California, both with a ratio of 3.0 psychologists per 100,000 population, Quintana Roo with 3.6, and San Luis Potosí with 3.7.

Table 2 and Figure 2 show detailed information on the number and ratio of psychologists in the public sector by state, their institutional affiliation, setting, and the geographic location of the centers where they are employed.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study presents an updated analysis of the distribution of mental health providers, specifically psychiatrists and psychologists, working at Mexican public institutions. This information is crucial for understanding Mexico’s mental health treatment gap, reflected in the discrepancies in healthcare access in society (Riley, 2012). In the following section, we compare our results with those of previous studies and international recommendations, assess the availability of public mental healthcare services across the country, discuss the limitations of the study, and conclude with final remarks.

The ratio of Mexican mental health providers at public institutions falls significantly short of international recommendations. With only 1.1 psychiatrists per 100,000 population (Table 1), it fails to meet even the recommended minimum of five to ten psychiatrists per 100,000 population, widely criticized as insufficient (Burvill, 1992; FCRS, 1962; Heinze et al., 2019; WHO, 2014). Although there are limited data available on the minimum ratio of clinical psychologists required to meet population needs, a study in Ireland recommended a minimum ratio of 17.3 per 100,000 population (Byrne & Branley, 2012), more than twice the 6.6 ratio of psychologists in the public sector found in our study (Table 2).

Moreover, a considerable disparity between states was identified, which can be seen in Figure 1. Approximately 34% of psychiatrists at public institutions work in Mexico City, which is only home to 7% of the total population, while 21 out of 32 states (comprising 70% of the total population) have a ratio of one public sector psychiatrist per 100,000 population or less (Table 1). Furthermore, most public sector psychiatrists are concentrated in urban areas (Figure 1), underscoring the barriers to mental healthcare in rural areas. Although the regional disparity in public institution psychologists appears less pronounced, we found a wide range of state ratios, from 3.0 to 14.4 per 100,000 population (Table 2), as well as a concentration in urban areas (Figure 2). The disparity in the distribution of mental health providers across states and regions is a complex issue influenced by healthcare system infrastructure and social determinants (Mohammadiaghdam et al., 2020). Key factors include state-level funding disparities, a higher concentration of secondary and tertiary health care facilities in large metropolitan areas, financial constraints, career opportunities, working conditions, personal choices, cultural norms, and regional living conditions, which affect service availability and raise safety concerns. To redress the balance, a comprehensive strategy addressing these factors is essential for equitable, effective mental healthcare resource allocation across Mexico.

Our findings regarding mental health provider ratios contrast with previous reports, such as the one by the Global Health Observatory of the WHO (2019) reporting ratios of .2 psychiatrists and 3.4 psychologists per 100,000 population in 2016. Given the relative stability of the public health workforce in Mexico over the past decade (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 2021), it is conceivable that the 2016 calculation omitted certain institutions within the complex Mexican public healthcare system. Alternative reports, including both private and public sector professionals, have estimated ratios of 3.7 psychiatrists (Heinze et al., 2019) and 53.7 psychologists (Secretaría de Economía, 2023) per 100,000 population in Mexico. Nevertheless, we suggest that our estimates reflect mental healthcare accessibility more accurately, as only a small proportion of the Mexican population can routinely access private healthcare services due to financial constraints (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 2021; WHO et al., 2020). Interestingly, comparing our study with those previously mentioned shows that in Mexico, approximately 30% of all psychiatrists and 13% of all psychologists work at public institutions.

Public institutions in Mexico vary considerably in their use of mental health providers. Specifically, 55.9% of all public sector psychiatrists and 78.9% of public sector psychologists work within the SS, which is primarily responsible for providing healthcare to the uninsured. Conversely, IMSS employs 25.9% of all psychiatrists at public institutions and 6.3% of psychologists at public institutions despite offering insurance coverage to nearly half the Mexican population. Additionally, ISSSTE employs 7.2% of all psychiatrists at public institutions and 2.4% of psychologists at public institutions while providing insurance to a sixth of the population. Age-related disparities in mental health provision in Mexico may arise due to the different demographics covered by IMSS and ISSSTE. IMSS insures a younger adult population, whereas ISSSTE covers a higher proportion of older adults. This variation in coverage could imply specific mental health care needs and a variety of approaches required for the various age groups across the country.

While national and international reports have highlighted the cost-effectiveness and improvements in accessibility and quality associated with the shift from hospital-based to community mental healthcare services (Díaz-Castro et al., 2020; PAHO, 2017; Secretaría de Salud de México, 2023a; Wong et al., 2022), our findings show a high concentration (83.3%) of state psychiatrists at inpatient facilities. It is worth mentioning that although inpatient clinics in Mexico tend to include outpatient services (such as a psychiatric hospital with an outpatient consultation department) (Díaz-Castro et al., 2020), and the hospital units included in our analysis are not necessarily designed for patients suffering from mental health or substance use disorders, this unbalanced prevalence of specialists in hospital settings reflects poor resource allocation for community care. This tallies with the findings of a 2013 study, reporting that 80% of the public mental health provision budget in Mexico is earmarked for psychiatric hospitals (Berenzon Gorn et al., 2013). Appropriately, current Mexican policies have focused on enhancing community mental healthcare services and the training of non-specialized personnel to reduce the diagnostic and treatment gap in mental health and substance-related disorders (PAHO, 2017; Secretaría de Salud de México, 2023b).

In terms of limitations, although our study maps the distribution of mental health providers in Mexico, it is important to note that merely quantifying the number of these providers does not fully reflect the mental healthcare gap. This gap is compounded by multifaceted barriers, including deep-rooted stigma, societal misconceptions, and a general lack of mental health awareness, which can deter individuals from seeking help. Additionally, structural issues such as inadequate healthcare infrastructure, especially in remote or underprivileged areas, as well as the lack of coordination between institutions and levels of care, hinder accessibility, and may lead insured individuals to seek help outside their designated institutions. These barriers, at both a personal and systemic level, require a broader, more integrated approach to mental healthcare that goes beyond merely increasing the number of healthcare providers.

In short, our study describes the acute mental health provider shortage in Mexico’s public health sector. This deficit significantly hinders access to mental health services, resulting in the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of severe, prevalent mental health and substance-related disorders. These consequences, in turn, contribute to diminished quality of life among affected individuals and their loved ones, and higher rates of disability, violence and social exclusion. A considerable regional disparity between Mexican states was also highlighted, contributing to the inequity of mental health services across the country. Our study highlights the urgent need to strengthen Mexico’s public mental healthcare provision. This includes increasing funding for mental health programs, improving coordination across healthcare institutions, and integrating efforts from various sectors to reduce stigma and boost mental health awareness. The development of community-based services and continuous training for non-specialist primary care providers is also crucial. These initiatives could potentially mitigate the disparities and barriers identified in mental healthcare, contributing to a more equitable and effective system, although their success will depend on effective implementation and continuous evaluation.